Including marginalised people in ‘people-centred health systems’

How do ‘people-centred health systems’ incorporate marginalised groups?

Older models of health systems research tended to focus on the core elements, also known as ‘building blocks’ or ‘hardware’, for understanding and shaping the system – financing, health workforce, governance, medicines and other supplies, services and information systems. More recent work has explored the software of health systems, which have been described as the ‘institutions (norms, traditions, values, roles and procedures) embedded within the system’. The relationship between the hardware (the provision of clinics and medicines etc) and the software (the desire to address marginalisation or create programmes for specific health issues) are mediated by power relations. Social accountability offers a mechanism for health system users to reveal, review and redirect these power relations to achieve more equitable health outcomes.

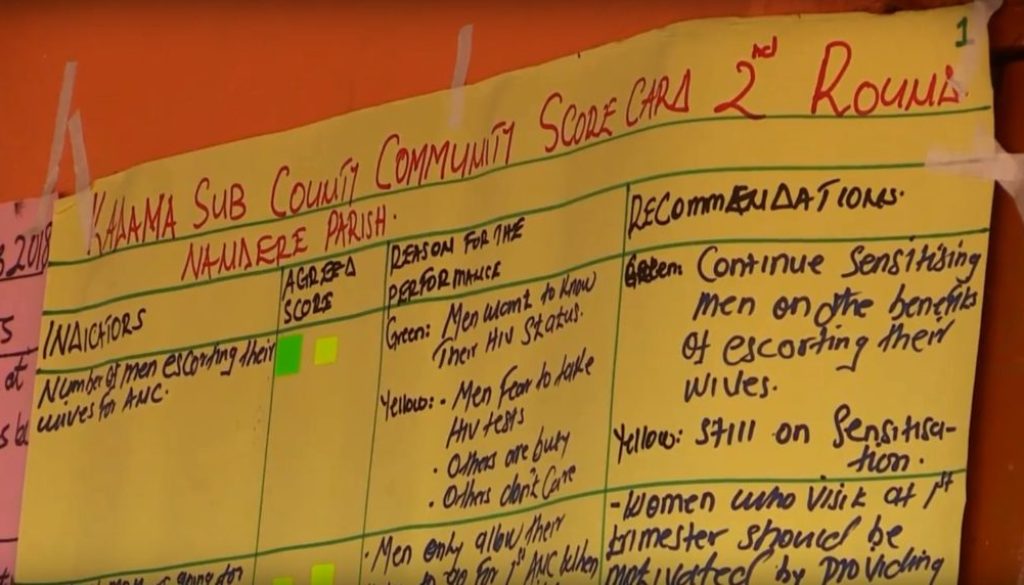

Tools used to encourage social accountability include: citizen report cards, participatory monitoring, social audits, public hearings, and community scorecards. For any of these tools to be effective, there is a need for citizens to engage and demand accountability. Yet not all citizens are in the same position or equally able to do this: power relations also limit voice and decision-making space.

Women with disabilities

Emerging research from RinGs shows that women with disability may be marginalised from local accountability mechanisms. In Kenya women with disabilities were not asked to be part of public participation forums because people thought they couldn’t access the venue and/or considered them uneducated. As one visually-impaired woman explained,

“There are public meetings of certain kinds that we are excluded from. That’s why you find that if we go to hospitals we don’t know even where to start…we have never been invited and told this and that or gathered together with others and told these are the developments, so you find some of us are discriminated against.”

In Kibuku district Uganda, research examined the community scorecard processes and the opportunities for women with walking disabilities to be included. It found that there are no provisions within health facilities to cater for women with walking disabilities – there are no ramps so women have to crawl up the steps, there is no suitable seating so women are sitting on the floor. Here is how one woman described using the toilet,

“Our health facility does not have separate places of convenience for the disabled people. I used to go to those available but I would often find them dirty … but I had nothing to do. I would still crawl in that messed up place like that.”

These women are also excluded from accountability processes because of the difficulties they experience in securing transport. As shown in the comments above, this reinforces their exclusion, discrimination and humiliation within the health system and limits their ability to make the health system more accountable to their needs. This cannot be allowed to continue.

Moving beyond the one-size-fits-all approach

Accountability mechanisms often focus on homogenous categories of users, which can result in certain categories being elevated to the norm (i.e. male, urban, educated, heterosexual users). When an attempt is made to include ‘marginalized’ groups, token individuals – such as poor women, disabled men or adolescents – are often included to represent an entire group of ‘marginalised’ people. At the same time, little effort is made to ensure that their participation is meaningful. For example, young women may not feel able to speak up if certain men (e.g. male family members or male partners, or men who occupy a supervisory position) are in the room, or a disabled woman’s unique experience of discrimination may be disregarded for the sake of consensus. The inability of some citizens to effectively participate, or the lack of inclusion of certain citizens, means that needs and experiences specific to them are unlikely to be addressed in improvements resulting from social accountability processes.

Accountability offers communities the opportunity to influence health systems, making them more responsive to local needs. Yet, as the examples above demonstrate, there is a very real need for health systems researchers to take a critical look at social accountability mechanisms, to examine if and how marginalised people are included in such processes. This might include forming more nuanced, precise and contextually appropriate definitions of marginalisation (potentially in communities that already have poor and marginalised populations). We need more reflection on those accountability mechanisms that have been shown to work in relation to inclusion of marginalised peoples; on accountability mechanisms that move beyond tokenism and address power relations within communities and between communities and health systems. We need to be better aware of potential barriers to inclusion and how to overcome them.

There is a lot of talk about ‘people-centred health systems’ but if our accountability mechanisms only cater to certain types of already-privileged people, it seems unlikely that they will take us further towards social justice.

By Kate Hawkins, Linda Waldman, Rosemary Morgan, Sabrina Rasheed, Rebecca Racheal Apolot, Chandani Kharel, Sushil Baral, Kunle Alonge